Vancouverites engage in a lot of dangerous activities. People are always skiing and hiking and and paddleboarding and slacklining and doubles-kayaking to and fro. Our active lifestyle means that along with tiny dogs and multi-prefix coffee drinks, slings and crutches are common accessories for many West Coasters.

Though the science of healing has always fascinated me, my curiosity peaked recently when I crashed my bike (okay, drunk-crashed my bike) in North Vancouver. As I fell, I remember thinking “I wonder which bodily configuration will result in the least damage when smashed against the Dollarton Highway at 35 km/h” and also “I wonder how healing works”

In the weeks following the crash, as my gross wounds knit and disappeared, I became more and more fascinated with regeneration. Human healing flies in the face of entropy, reordering and reestablishing tissues in a complex cascade of events.

The bloodhound

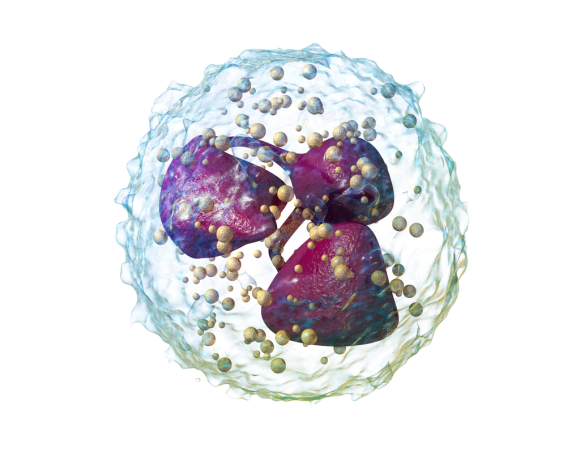

Let’s hop on the back of a white blood cell as it circulates through a body, perhaps as this body hurtles through North Van on a full-suspension mountain bike, wearing lights and helmet, MOM. This particular white blood cell is called a neutrophil. Neutrophils are the first-responders to a wound, and play a crucial role in healing- it’s no wonder that your body solicits over a hundred billion of them from your bone marrow every day.

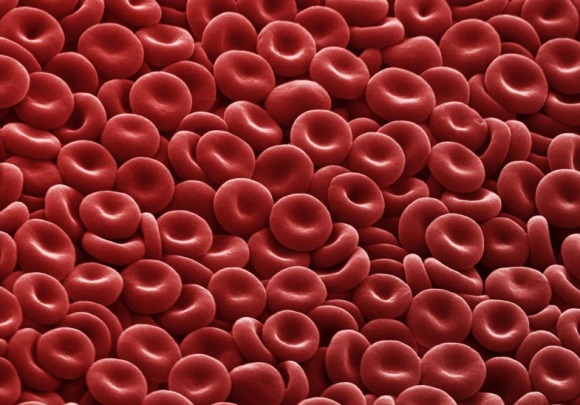

As it courses through the body, the neutrophil hunts for evidence of molecular foul play. It continuously samples blood plasma, searching for signals emitted by distraught tissues. Its senses are finely tuned to the chemical flavour of the blood, and even the slightest deviations are detected immediately. It floats in a sea of red blood cells, calm and contemplative.

Crash and wound

The biker hits a patch of gravel as he leans into a turn, and falls. He expels a quiet bark of air on impact, a sigh of defeat in the hopeless argument with gravity.

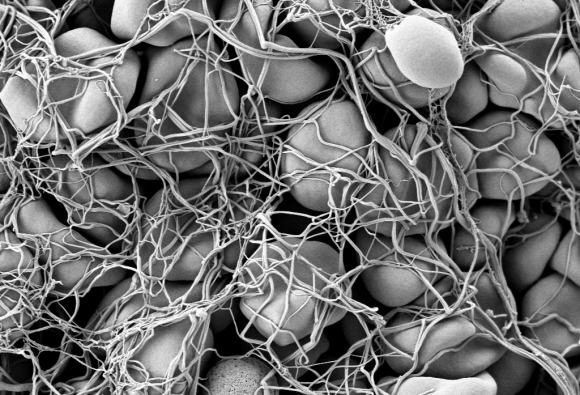

As the biker tumbles and stutters to a halt along the highway, red blood cells pour into the fresh wound. Collagen fibres, the rebar of the skin, illicit a sharp molecular bark in response to the taste of blood. This shockwave ripples through the red blood cells and raises their cellular hackles. Alarmed, they begin to exude sticky glycoproteins, clumping and cementing together.

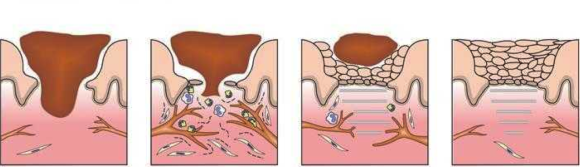

Within seconds, the red blood cells have grown molecular hands, appendages that pluck proteins dissolved in the blood and craft them into hard, solid fibres. These fibres form a ramshackle mesh that traps more red blood cells. This ad hoc plug of fibres and blood cells is the beginning of a scab.

The alarm

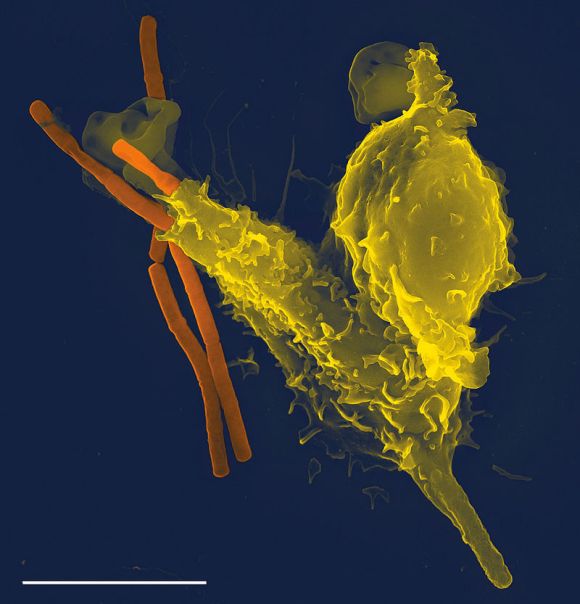

Elsewhere in the body, the neutrophil senses trouble. Among the thousands of complex receptors on its surface, several have detected faint distress signals. From these communications, the neutrophil assembles a chemical map to navigate towards the wound. It traces minute gradients of substances, leveraging concentration differences of less than one percent to decipher the correct path. As it travels closer to the wound, the signals become stronger. The neutrophil begins to change shape, morphing from naive sphere to predatory corpuscle.

The neutrophil arrives at the site of the injury. The gash rivals the Grand Canyon in proportion, a vista of dead cells and jagged dermal framework. Before any healing can begin, the neutrophil must raze and scour the entire wound surface. The scale of the task is staggering, and the clock is ticking.

Already, opportunistic pathogens have alighted, bulbous and hungry. Bacteria and fungal cells blunder across the bloody landscape, gorging on cell entrails and corkscrewing into the ramshackle blood cell matrix. Viruses latch onto cell walls, injecting contagious DNA. Left unchecked, the pathogens will duplicate and fester; it is cellular chaos, and it is the neutrophil’s responsibility to tame it.

Luckily, our neutrophil is not alone. With every heartbeat, thousands of additional neutrophils arrive to the scene. Each employs a powerful array of antimicrobial tools to battle microfauna: caustic chemical sprays, sticky trap-nets of DNA, and gaping jaws. It is an unfair fight, and it ends quickly.

Full to bursting with liquefied pathogens and recycled cell parts, the neutrophil sits in the wound, awaiting death. Alongside millions of other neutrophils amassed in a jellied poultice over the wound (pus), it will be consumed itself, its neutralizing responsibilities complete.

Regeneration

The next cells to arrive are macrophages, and they are here to eat spent neutrophils. Macrophages (Greek: big eaters) also stimulate cells in the wound to begin regenerating blood vessels and collagen.

As the macrophages set to work digesting neutrophils, new blood vessels snake across the surface of the wound, pseudopod projections from healthy skin nearby. Over the matrix of blood vessels, specialized cells lay down a basketwoven lattice of collagen. Collagen is the substrate on which skin cells grow, providing structure and growth stimulus.

Once a blood supply is established and a collagen frame mapped out, skin cells begin to regrow. Daughter cells bud from mothers to fill in adjacent collagen plots, each cell tripling every hour. Sheets of cells are layered with more blood vessels and collagen. The basement of the wound begins to rise, growing at 0.5mm per hour.

As the gash becomes shallower, smooth muscle fibres at the wound edges contract and pull together. Unused blood vessels are dissolved, while new vessels irrigate the fresh tissue with nutrients and steroids. Hastily constructed collagen fibres are reorganized and chemically treated to strengthen the cellular framework. In the weeks following, the skin will mature and strengthen to its original state, leaving no evidence that damage ever occurred.

Fin

As the wound heals, the inflammatory signals fade and life in the skin returns to its half-dead normal. Healthy cells that were once instrumental in the healing process die and take their place on the skin surface, eventually sloughing off to be swept or vacuumed up by cleaning apparatus of a larger scale.

Don’t drunk bike, guys.

One of my favourite sci-fi authors, Peter Watts, has posted pictures of his battle with Flesh-Eating Disease on his blog. If you’re like me, you’ve seen a lot of really horrific and disturbing photos on the Internet; these are by far the most horrifying photos I have EVER SEEN. Check them out here:

http://www.rifters.com/crawl/?p=1848

http://www.rifters.com/crawl/?category_name=flesh-eating-fest-11

3 replies on “How Does Skin Heal?”

Your writing is so refreshing Stu.

[…] a woman goes to the doctor because she crashed while drunk-mountain biking home from her buddy’s birthday kegger and tore all the cartilage that attaches her collarbone to her shoulder, as has been known to […]

[…] that it all of this has FUCKED. ME. UP. I just wanted to write about raccoons and baking soda and how exactly skin heals, but now I feel a real and pressing need to focus all of my mental capacity on buttressing […]